We recently helped a keen developer and a longstanding nightclub find a ground-breaking solution to a potentially noisy standstill. Chris Borak, our Bristol-based Acoustic Engineer, led our approach, and here he explains how quality residential developments and cultural venues can rub shoulders without butting heads.

My line of work means I’ve often found myself embroiled in an unending battle for prominence in city centres. On one side: developers of residential buildings, and on the other: the owners of night clubs, pubs and other music venues. The problem? Nuisance. The noise generated by music venues can cause problems when it affects someone in their home.

The concept of nuisance has existed in common law for around 200 years. In general terms, it’s caused when the action of one person causes some form of significant harm to life, health, property, comfort, rights or enjoyment of another person. Noise is a common cause of nuisance complaints. When the resident of a new dwelling in an urban area complains about noise from a music venue, it has for the most part been considered irrelevant that the venue predated the dwelling. The likely outcome is that restriction will be placed on the source of the noise, which for the music venue, could lead to closure.

A battle between commerce and culture?

It’s easy to see why music venues get nervous when they see a planning application for a new residential development close by. I’ve been involved in a number of cases in Bristol and beyond where, in an attempt to prevent the worst, the venue’s reaction is to rally public opinion against the development through social media. These cases often end up getting characterised as a battle between a commercially driven developer who wants to turn everything into a housing estate and the cultural heart of the city or town.

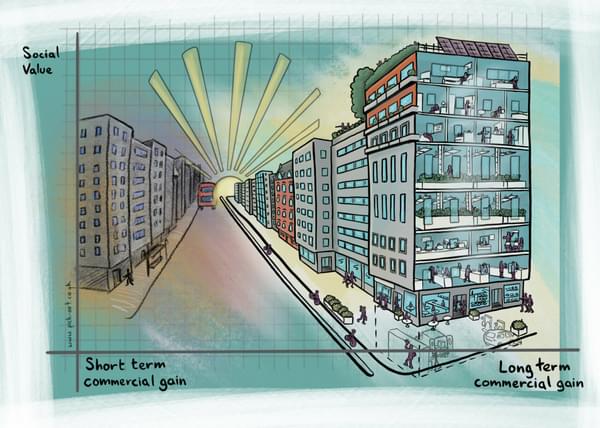

However, the vibrant nightlife and culture of any city is absolutely crucial to its desirability and value as a place to live. Furthermore, music venues and other night-time entertainment venues benefit from the footfall provided by high density residential developments. Therefore, developers and venues often have much more common ground in terms of their business interests than it might seem at first glance.

The planning system and local authorities do and should look to ensure that new residential developments consider noise from music venues and the night-time economy more widely. A recent change to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) reiterated the point that a person or business introducing a new land use (i.e. ‘the agent of change’) should be required at the planning stage to provide mitigation suitable to avoid nuisance complaints that could ultimately lead to unreasonable restrictions placed on the existing business.

Moving towards a solution

Hydrock has recently helped the developer of a proposed residential scheme on Silverthorne Lane in Bristol obtain planning permission. The site is part of a wider masterplan for the redevelopment of this area of east Bristol. The whole area is affected by noise from the Motion nightclub which has, up to this point, been operating in a relatively undeveloped and uninhabited part of the city. Motion has operated here for many years and is regarded as an important cultural landmark.

Motion were understandably very concerned about the development and how the changing character of the area would affect their business. The nightclub rallied its loyal, music-loving troops through social media, hundreds of objections were received and petitions signed asking the local authority to refuse the planning application. Motion suggested a Deed of Easement (DoE) similar to the one used by The Ministry of Sound in 2013.

“This is the first time in UK history that a requirement for a DoE has been placed as a condition of planning.”

A Deed of Easement essentially prevents future residents of the proposed dwellings from making nuisance complaints relating to noise from Motion.

It was not possible to agree the DoE conditions before progressing the planning application as there was no clear agreement on what the existing noise levels from Motion were and, at the time, all potential mitigation options had not been fully explored.

Therefore, new conditions were drafted and suggested to Bristol City Council, which would require engagement between both parties and agreement of a suitable DoE. This is the first time in UK history that a requirement for a DoE has been placed as a condition of planning. This isn’t straightforward to do, as it requires serious engagement from both parties. In my view engagement between music venues and developers is absolutely vital to developing vibrant, sustainable, mixed-use city centres.

A delicate balance

From my involvement with the Silverthorne Lane scheme it has been clear that the developer fully understands the importance of Bristol’s music culture to the value of its assets. Flats in Bristol simply would not be in as high demand as they are if it wasn’t for the city’s vibrant music scene and culture. Developments like Silverthorne Lane are viable in Bristol because music venues like Motion make it an appealing place to live.

The most vibrant, interesting and valuable areas of the city are those where residential buildings coexist with successful day-time and night-time trading. Personally, it was the culture, life and sounds of such places that first attracted me to Bristol and made me fall in love with the city. While noise from railways and roads will almost certainly devalue a residential property, this is not always the case for noise from entertainment venues and leisure activities. For example, a two-bedroom flat in the “noisy” centre of Bristol, in vibrant areas like Stokes Croft, can cost as much as a four-bedroom family home in a quiet suburb.

It’s also important to remember that successful night-time entertainment venues in a sustainable town or city need the footfall that comes from high density residential developments. Motion, for example, simply could not exist in a leafy suburb. Therefore, unless we can expect a largely industrial or vacant area of the city to remain undeveloped due to the noise of a music venue, solutions for coexistence must be found. I see our role as acoustic engineers as finding a way for the two uses to thrive in close proximity without friction.

“I see our role as acoustic engineers as finding a way for the two uses to thrive in close proximity without friction.”

Engineering sound solutions

This actually isn’t terribly hard to do from an engineering standpoint. Some years ago, I had the opportunity to work on a scheme to develop a brand-new music venue and flats within the same relatively small site. With control of the design of both elements it was quite possible to mitigate noise to acceptable levels at much smaller separation distances than many assume is possible. It was also possible to actually enhance the acoustic environment of the wider area and design a soundscape which enhanced the feeling of vibrancy, while allowing residents to enjoy peace and quiet when desired.

The agent of change principal places the onus on developers to provide mitigation. This is often most effective and successful if it is done at source, such as improvements to the music venue building, rather than relying on the sound insulation of the residential building alone. Therefore, developers and music venues need to come together to provide the best solutions.

With the Silverthorne Lane planning conditions, Hydrock and the developers have been able to combine a requirement to come together and discuss the best solution to build a vibrant mixed-use area of the city with the legal assurance for the existing music venue provided by a Deed of Easement. Great care in drafting the conditions was required to ensure neither party was tied in to unacceptable terms, and the resulting solution can form a basis for other similar projects in cities and towns across the country.