“It’s a chilly evening on the fringes of the Northern Quarter ‒the kind when you can see your breath in front of you. Just hanging there. The absence of footsteps and laughter is unsettling, a silence broken only by erratic fits of wind rattling the shutters of closed doors.”

It’s a chilly evening on the fringes of the Northern Quarter ‒the kind when you can see your breath in front of you. Just hanging there. The absence of footsteps and laughter is unsettling, a silence broken only by erratic fits of wind rattling the shutters of closed doors.

Manchester was always the exciting big city up the road. Growing up in sunny Stoke-on-Trent, my family and I would visit a couple of times a year to go shopping, eat good scran and, if I was lucky, to see a show or concert. In fact, my first proper ‘gig’ was Robbie Williams at Trafford Park.

As I grew older, Manchester became increasingly synonymous with music; Manchester Academy being one of the nearest (and best!) places to see bands outside of Stoke, and also where I most enjoyed gigging myself before I jacked in music for a ‘real job’ in acoustics. It’s no coincidence that I now call this city home.

For an era, Manchester defined the UK music scene. Spend any amount of time here and you won’t be able to ignore that it started with the Hacienda, which went on to have a profound effect on the way clubs looked by swerving traditional nightclub stylings in favour of a disused warehouse setting that became a magnet for musicians, creatives and people from all walks of life. Its heartbeat, some might say.

Then, in the nineties, regeneration swept through the city. Commercially-driven developments and gentrification eroded away at underoccupied buildings and quietly killed off some of our city’s cultural and music venues, including the Hacienda which has since become the site of residential apartments.

Now, given my love of music, as an engineer, I’m interested in how sound interacts with the physical buildings around people’s everyday lives.

“Now, given my love of music, as an engineer, I’m interested in how sound interacts with the physical buildings around people’s everyday lives.”

The introduction of new residential developments in a vibrant urban setting usually introduces some level of conflict. It only takes one resident to make a nuisance complaint for restrictions to be placed on the source under common law ‒how is that fair?

An example of this was the row between Night and Day and a neighbour in a new-nearby residential building, attracting national attention and a petition signed by Manchester’s own Johnny Marr. The debacle could have been avoided had the acoustic design been considered appropriately. Most acousticians are musicians in some form another, so these projects are close to our hearts and we’re invested in finding ways for them to co-exist.

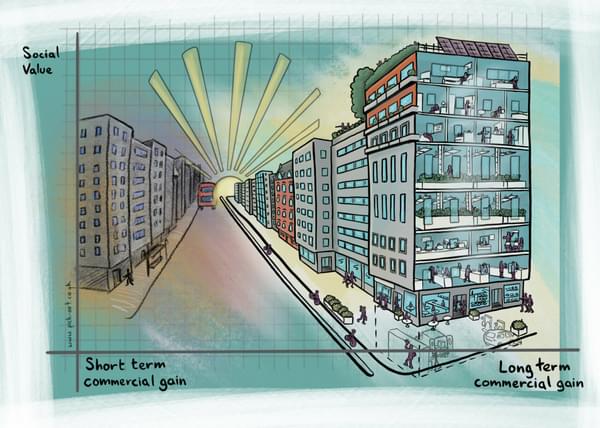

Of course, people need places to work and live, but maintaining the desirable characteristics of the city centre is critical to value. Who wants to live in a city with no pubs, theatres or music venues? Most developers recognise this mutual interest, in my experience. But it’s a real balancing act.

“Of course, people need places to work and live, but maintaining the desirable characteristics of the city centre is critical to value. Who wants to live in a city with no pubs, theatres or music venues? Most developers recognise this mutual interest, in my experience. But it’s a real balancing act.”

Local authorities must ensure that new residential developments widely consider noise from music venues and the night-time economy ‒because context is everything. A change to the National Planning Policy Framework reiterated the point that a person or business introducing a new land use (i.e. ‘the agent of change’) should have a strategy to avoid nuisance complaints that put otherwise viable existing businesses at risk.

Hydrock recently consulted on a ground-breaking project involving Motion nightclub and a nearby residential development. The result was a Deed of Easement ‒the first of its kind to be secured via planning condition, which has set planning precedent. In the end, all parties collaborated to find the best solution for a vibrant mixed-use area of the city, while providing the legal assurance for the existing music venue.

I’ve also been providing acoustics consultancy to the Northern Quarter’s historic music venue, Band on the Wall, on its £3.5m expansion project to up capacity from 350 to 530, increasing opportunities for people to engage with Manchester’s rich musical culture and bringing more artists to the city. That hits the nail on the head for me, with every new city-centre development good design and acoustic engineering is critical to sustaining the culture, life and sounds of the city.

Manchester is one of the fastest growing cities in Europe. With a £9bn visitor economy, its post-dusk reputation and inimitable brand of edge clearly still holds huge pulling power.

Make no mistake, the pandemic and consequent restrictions imposed have hit this city hard. Even before the latest lockdown measures, it’s believed to have cost Greater Manchester 61 per cent of that visitor economy value. Independent “wet-led” pubs, like The Castle Hotel and Port Street Beer House, are really up against it now. For me, this is a disaster, because they are the gems in the crown of a city centre and need to be protected through this truly awful pandemic to prevent a cultural void being left in our city.

At its vanguard, Sacha Lord, the Night Time Economy Adviser for Greater Manchester, has taken a stand. This includes action against the UK government and the launch of the Greater Manchester Night Time Economy Recovery Plan. This sector, which accounts for in excess of 420,000 people across Greater Manchester, needs support from government, including greater transparency about the restrictions being imposed and a blueprint for moving forward.

The government has suggested that freelancers and people working in creative industries should “adapt” their jobs during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. In my view, it’s a nonsense and insulting.

Towards the end of 2020, I tuned into a Forum for the Built Environment webinar on the ‘The Arts’ Perspective’ which among many discussions highlighted how critical it is for the government to get the lifting of local lockdowns right this time. The general consensus being that clear and early engagement with these industries is key.

Something that really chimed during the webinar which, alongside the aforementioned Sacha Lord, featured Liz Pugh (Walk the Plank), Tim Heatley (Capital & Centric) and Martyn Evans (U+I), is that we are part of a community that’s in it together.

Through close collaboration, the arts, culture and entertainment industries are looking for ways to take advantage of the “Then” of the world before COVID-19 and the “Now” moment in which we live to create connected, inclusive spaces.

“Through close collaboration, the arts, culture and entertainment industries are looking for ways to take advantage of the “Then” of the world before COVID-19 and the “Now” moment in which we live to create connected, inclusive spaces.”

There are many reasons to be optimistic, knowing people won’t let go of their passions. I for one can’t wait to get back into the pub, to watch a gig or to see a show.

This article was originally published on Place North West in November 2020