We caught up with our Principal Sustainability Consultant, Mohammed Khan, to talk about the connection between mental health and access to daylight in the built environment, plus the ever-increasing significance of fuel poverty in the UK and how we need to address these issues...

In the ever-sprawling context of urban life, we often forget that we are, in fact, just over evolved mammals. Far from Mother Nature’s plans, we’ve now developed our species to the point that we’re spending the majority of our day in the most unnatural of environments possible.

Skyscrapers with sleek, engineered aluminium façades. Spacious distribution warehouses with thousands of metres of floorspace. Majestic university halls with historic, aesthetically pleasing wood-cladded walls. Whatever the purpose, there’s a unifying truth: if we don’t get the natural daylight or fresh air that we’re designed to have, then we’re going to suffer.

“Humans now spend nearly 90% of their time indoors, so, it’s not surprising that mental health is on a serious decline.”

Natural daylight is fundamental for our sleep quality, mood, productivity and overall mental health – it’s one of the most crucial elements of a building’s design. Yet when you take a look at many of the spaces we have for our offices, education and even living, it’s often overlooked.

I’ve found studies into natural daylight fascinating since school. Even at that age, it was clear to me that we don’t get enough of it. Schools, colleges and universities are often set within old buildings and, therefore, they’ve very poor lighting in addition to no or very little ventilation. Sat in a classroom with that kind of environment, you’re more likely to be preoccupied with clock watching than concentrating on learning.

When I reflect on my own time in school, I don’t think we had the best environment for health and wellbeing. I remember frequently being unable to open windows, there wasn’t any ventilation, natural or mechanical, and I often felt hot and stuffy — this had a detrimental effect on our learning. It was a similar experience in one of the first offices I worked at, it just didn’t have the correct lighting and as a result my ability to work was affected. Migraines, eye-sight, energy… it’s not just our mental health that takes a hit.

“1 in 4 people will experience a mental health problem of some kind each year in England.”

So how do we fix this? An example would be a school campus. A pre-existing building on campus needs re-evaluating as the pupils and staff are not getting the correct environment they need. They’re getting far too hot in the summer and it’s affecting their studies. The best way to approach this is to undertake a passive design analysis which includes a daylight and sunlight survey. You need to drill down into what the building already offers, what it doesn’t and where improvements can be made.

For example, some windows in schools can’t be opened due to compliance with health and safety. So, in such a case, can mechanical ventilation be added? If that isn’t possible, or you don’t want to impact the building’s carbon footprint, what other solutions can be adopted?

You have limits with old buildings, but there’s always something you can do to make improvements. We have so many clever solutions these days — spectrally selective film could be installed on the windowpanes to keep the sun’s heat out, but daylight in. The roof of the building could be painted with special pigments, acting as a barrier to reflect solar radiation. In some cases, it’s been found that this can reduce surface temperatures by more than 10°C.

Take Martials Walk, in Knowle, Bristol, as an example. We were appointed by Bristol City Council to support the detailed planning application for the proposed pathfinder development of residential units. A key aim for the client was climate adaptation — developing energy efficient, low carbon buildings that are resilient to the effects of climate change. Along with natural ventilation for cooling, we also proposed the tactical planting of trees to provide shading from the sun, and a lighter coloured roof now helps to reflect solar radiation. These steps alone could also offer some aid to an existing development that needs to reduce overheating.

More schools, universities and colleges can start to resolve these types of issues in their buildings by tapping into SALIX funding. This is a funding stream that offers organisations within the public sector interest free funding for energy efficiency projects. Our team has recently prepared a Smart Energy statement in support of the planning application for the University of Cumbria’s proposed development at The Citadels, in Carlisle, where the university is applying for this type of funding to futureproof its estate.

Whilst we need natural daylight, too much can be detrimental and can affect the building’s internal temperature and lead to overheating. This goes the other way too, a building’s temperature can not only affect our mental wellbeing, but our physical health can be at risk too. Unfortunately, and especially in the current economic climate, more and more of us are struggling to heat our homes in winter, to the point where some people are having to choose between heating or eating.

I grew up and still live in Birmingham. It’s home. Over the years, I’ve watched the city evolve and I love how it’s adapting to the energy transition and embracing sustainable living. Local authorities are working hard on the heart of the city, and there’s a lot of development which has started to filter through into the suburbs too. However, even with all this fantastic progress, I feel the one thing that’s being overlooked, which I see as being the case across many cities across the UK, is fuel poverty.

“It’s estimated that 4.5 million households in the UK are living in fuel poverty, struggling to heat their homes.”

This is definitely the case for Birmingham and you can see some significant divides across the city. When you compare people’s standard of living in Solihull and Edgbaston to those in Sandwell and Sparkbrook — the difference is off the scale. If Birmingham wants to be taken seriously, then it needs to really tackle things like this. If it really wants to be the ‘place to be’ in the UK.

I’m a big campaigner on fuel poverty and affordable housing, and I think the government needs to up its game. This will undoubtedly be a priority for our latest prime minister. It’s easier said than done, but having a scheme in Birmingham similar to the GLA carbon offset fund could really help the alarming amount of people that can’t afford it. People need it, and with each winter that comes, it gets worse.

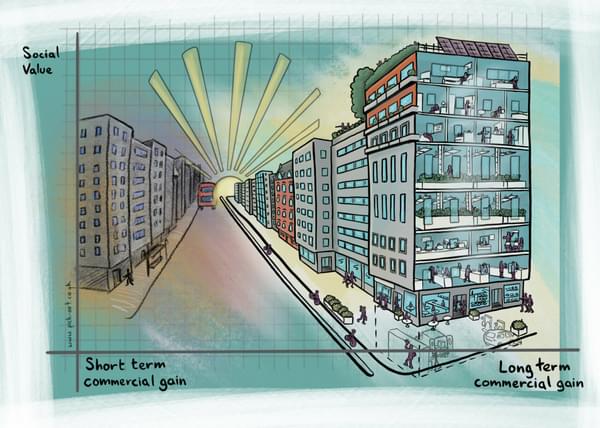

I know there’s no magic money tree, so that’s why Birmingham needs to put development targets in place to help create funds for social housing and those who need it. Ok, picture this; you’re a developer building a new housing estate in the area – the local authority requires you to reduce emissions by 50% for your development or, ideally, it should be net zero. If you fail to reach the set target, they will charge you a set amount per tonne of the residual carbon remaining to get the development to net zero.

The government’s already doing this in London, as set out in the London Plan 2021. It lays down strict requirements for developments to significantly contribute towards the city becoming zero-carbon by 2050. Within this agreement it’s recognised that should a development fail to reach these targets; the developer will be penalised with a price of £95 per tonne of carbon over a 30-year period. Although this may not work in every city where development is low, there’s no excuse for a thriving city such has Birmingham.

“The last government report shows that the West Midlands has the highest proportion of fuel poor households.”

It’s crucial that the new buildings our local authorities are constructing are well-designed and carbon mitigation needs to run through the very veins of every single project — from investors right down to the technical engineers who are designing them.

We can work to combat fuel poverty during the planning stages of our new homes, and developers need to take more responsibility for this. That means aiming higher than cardboard box homes.

Strong, optimised homes that can keep up with the dramatic changes in our weather. Homes that keep us warm in the winter, avoiding costly utility bills, but remembering that fuel poverty isn’t just around heating, with the push for air source heat pumps (ASHPs) it could lead to fuel poverty in cooling homes, and if this is the main strategy to prevent overheating then the consequences could be disastrous.

In the areas we’re redeveloping, it’s key that we optimise our existing buildings to their absolute potential. Again, take the University of Cumbria as an example —we’ve been working with the university since 2020 to develop their 2030 Carbon Management Plan and our team has recently worked on a number of exciting whole-building decarbonisation projects across each of the university’s five campuses.

Through our work, we’ve identified key enabling works, building fabric and plant replacement projects alongside comprehensive heat decarbonisation projects that could halve Scope 1 and 2 emissions before 2030. Not only will our work help rejuvenate campus buildings, but this highly sustainable action will help set the university apart as a leader, paving the way for other universities and education facilities across the country.

Through my work at Hydrock, I can already see some of the changes being made in developments and redevelopments up and down the country, but this only scratches the surface of the work that needs to be done.

I truly believe, to ultimately achieve happier people in Birmingham and across the whole of the UK, combatting fuel poverty and our access to daylight in the built environment are the two crucial elements to address. They go hand in hand, affecting us mentally and physically.

With winter fast approaching, and with the current energy crisis upon us, the government need to prioritise and act fast.

Mohammed is a Principal Sustainability Consultant at Hydrock based in our Birmingham office. Take a look at our Smart Energy and Sustainability page to find out more about his team and the services they offer across the UK.