Climate Adaptation

We’re living in a warming climate. Even in the temperate UK, the long-term implications of this are enough to keep property owners, estate managers and, frankly, the public awake at night. Even when the mercury isn’t at 40 degrees.

“ With respect to climate change, it’s imperative we design to manage the unavoidable as well as to avoid the unmanageable. ”

Rebecca Lydon

Associate, Smart Energy & Sustainability

We’re living in a warming climate. Even in the temperate UK, the long-term implications of this are enough to keep property owners, estate managers and, frankly, the public awake at night. Even when the mercury isn’t at 40 degrees.

Understanding the physical risks to real estate from climatic change, and the transitional risks in terms of reputation and value, will drive the case for climate adaptation strategies.

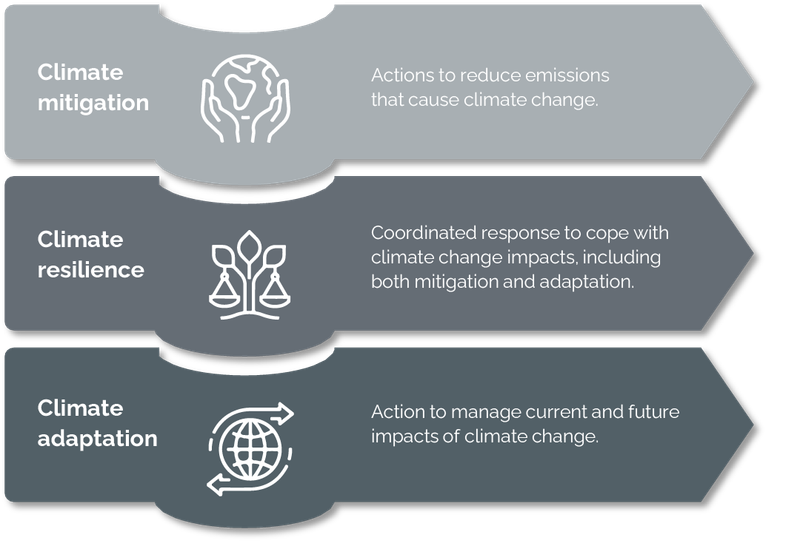

Defining climate resilience

Climate resilience is the ultimate goal. It’s a coordinated response to strengthen the ability to cope with and recover from climate change impacts. It combines actions on both mitigation and adaptation.

Society is increasingly familiar with climate mitigation measures. These are taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change. They typically include energy efficiency measures, investment in clean energy and more sustainable forms of transport. The concepts are established, the benefits recognised, but investment, central government commitment and behavioural change could all go further.

The spotlight is now on the other side of the same coin: climate adaptation – actions to manage current and future impacts of climate change. Predominantly, this is about how we use land and protect communities, buildings and infrastructure in the face of climate change impacts that are already locked in over the next few decades.

Why mitigation is not enough

Recent studies, backed up by the UN Environment Programme report published in October 2022, declare that there is no longer a ‘credible pathway’ to limiting global warming to 1.5°C based on current policy. Indeed, if the situation remained ‘business as usual’, the emissions trajectory points to a 2.8°C temperature rise by the end of the century, with implementation of current conditional and unconditional pledges only reducing this to between 2.4°C to 2.6°C above pre-industrial levels by 2100.

This means present day development and regeneration projects must respond to significant changes in the climate over their lifespan.

Current and future climate risks must be factored into the planning and design of projects in the built environment. For investors and users of existing built assets, it’s imperative to understand the potential impacts.

By way of example, unless we take further action, under a 2°C by 2100 warming scenario, annual damages from flooding for non-residential properties across the UK is expected to increase by 27% by 2050 and 40% by 2080 according to the UK Climate Change Risk Assessment report produced in June 2022. We simply cannot allow inaction in adaptation measures.

Understanding the risks

So, against this backdrop, it’s important for all organisations to understand the risks they face from climate change.

On a macro-level these climatic risks can be defined as:

- Acute risks of climate change: physical, event driven situations, usually weather-related

- Chronic risks of climate change: impacts of longer-term shifts in climate patterns

In terms of a vulnerability assessment of a business and its real estate, risks are classified as direct/physical risks and indirect/transitional risks.

Direct/physical risks include:

- Climate-related damage to buildings and infrastructure

- Financial impacts including loss of value, adaptation costs and repair

- Availability of affordable insurance

- Negative impacts to employees’ health and wellbeing from poorly performing workspaces

- Supply chain disruption with products or services unavailable due to climatic changes

Indirect/transitional risks include:

- Reputational damage from owning or occupying assets adversely affecting the climate

- Stranded, poorly performing built assets that have no value and impact ESG strategies

- Legal issues associated with inefficient real estate

- Non-compliance with emerging policies and mandatory regulation

- Increased competition for scarce resources

Planning for adaptation

A 2022 report by the London School of Economics (LSE) on climate change costs to the UK, predicts that under current policies the total cost of climatic damage to the UK will increase from 1.1% of GDP at present to 3.3% by 2050, and at least 7.4% by 2100.

Drawing this back to a micro-level, it’s important to prioritise adaptation measures based on a risk evaluation of every site, asset and business scenario.

Typical analysis of whether real estate is vulnerable to climatic change includes impacts of:

- Air temperature and humidity increase

- Extreme and prolonged periods of high temperature

- Increase in solar radiation

- Increased storm intensity and frequency

- Increased exposure to risk of flooding from greater rainfall patterns

- Increase in average and maximum wind speed

- Availability of water

- Availability of power

It’s a process that is estimating risk by examining issues such as:

- The expected lifespan of an asset

- Any planned future development

- Structural stability

- Weather proofing

- Durability of materials

- Ability to maintain affordable and available insurance

This type of risk assessment will prioritise actions and the costed recommendations to adapt and protect. Generally speaking, adaptation should be locked-in to deal with a 2°C rise in temperature with the risk assessed for up to a 4°C rise.

The goal is to reduce future risks and enable business continuity.

Emerging trends

Climate adaptation is a big subject. Planning now for scenarios in 50 to 80 years’ time is not easy, but in the face of quite evident climatic change, it’s of paramount importance.

A number of emerging trends help to offer shape and structure to the way ahead. These include:

- The emergence of UK Green Taxonomy: a common framework to classify all investments and their sustainability. It offers a route to consistency and transparency by providing a common set of criteria for investors to screen potential investments to determine if they deliver on key climate, social, green and sustainable objectives. This places an onus on organisations to focus on issues such as climate adaptation, mitigation, pollution control, biodiversity and the transition to a circular economy.

- Access to green finance: there is a plethora of funding and capital streams available offering ‘green finance’ to connect to projects. The opportunity lies in making a compelling and fully costed business case to access these funds.

- Mandatory disclosures: Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) is already established for around 1,300 of the largest organisations to produce non-financial disclosures of their climate related risks and opportunities. Energy usage and emissions is the declaration that nearly 12,000 organisations are making under the Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting (SECR) initiative. These very public disclosures encourage transparency, scrutiny and action.

- Recognising interdependencies: engineering skills will help overcome the obvious unintended consequences of some potential solutions. For example, combating overheating in properties by installing comfort cooling is simply creating urban heat islands from the rejected heat and adding to emissions. Finding clever techniques to overcome unintended outcomes is why engineering is so closely allied to the sustainability agenda.

- Valuing a just transition: increasing inequality is a major threat as a result of climatic change. Typically, lower income households will be more exposed and impacted by change. A number of metropolitan local authorities in the UK are recognising that there is a real cost benefit to be achieved from addressing the social costs of emissions and pollution. Putting plans and policies in place to support a just transition to a zero-carbon future delivers a more socially equitable future with better return on investment for all stakeholders.

- Nature-based solutions: As developers respond to the mandatory requirements for biodiversity net gain, and the emergence of environmental net gain, so some of the societal challenges from climatic change can be addressed. Our health and wellbeing, access to water and shading from increased temperatures are side-benefits from commitments made to improve the natural environment through more green space, better drainage systems, clean air zones and more woodland.