From being labelled a human rights issue, a health risk and even the subject of a national day, it seems like we’re all talking about air quality at the moment. And understandably so – with growing public awareness of environmental issues, and over half the world’s population living in urban areas or cities, it’s an issue that affects many of us. Public interest in air quality picked up significantly in 2015, when the ‘dieselgate’ scandal saw the whistle blown on vehicle manufacturers who were found to be using defeat devices to fiddle emissions tests.

Air quality is a complex issue, and ongoing scientific studies are constantly shedding new light on our understanding of air pollution and its effects on us. Yet the results of these studies aren’t always widely shared, and as the international conversation around air quality has grown, several myths have gained traction, despite not actually being true.

Myth 1: “Air pollution is worse now than it ever has been.”

You’d be forgiven for thinking that air pollution in our cities must be at peak levels – sensationalist headlines certainly seem to suggest it. However, studies have shown that, on average, pollution concentrations are actually at their lowest level since records began. If you’re a data sort of person, you can see this on the graph below. Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is the predominant emission from car exhausts. In 2019, a Defra report showed 2018 had the lowest ever recorded annual mean concentrations of NO2. Levels of NO2 measured at city roadsides have dropped steadily in the last 20 years (see graph below). This is because, whilst the volume of traffic has increased, vehicle emissions have improved dramatically in comparison with the 1990s and 2000s.

Myth 2: “Cars protect us and our children from rush hour pollution.”

While it seems logical that sitting inside a closed vehicle would offer greater protection from external pollutants, this is another common misconception. A number of studies have compared pollution levels for different modes of travel in busy cities, with the overwhelming conclusion that pedestrians and cyclists are exposed to less pollution than those in vehicles (see graph below). As cars take in air through fans in close proximity to the exhaust of the car in front, sitting in traffic can pose a health risk to all passengers. Research led by Professor Stephen Holgate of Southampton University found that pollution levels in cars can be nine to 12 times higher than outside.

Myth 3: “Clean Air Zones will tackle pollution in our cities.”

The government is spending £260 million on Clean Air Zones frameworks, which sounds impressive, but means people will have to pay money - either to drive their heavily polluting vehicle into the city, or fork out for a new, “cleaner” car.

Road pricing based on vehicle emissions encourages companies and the general public to swap older, more NOx emitting vehicles with newer ones that have bigger catalytic converters. However, in many cases these new vehicles are bigger, and actually less fuel-efficient than older cars, thus increasing CO2 emissions.

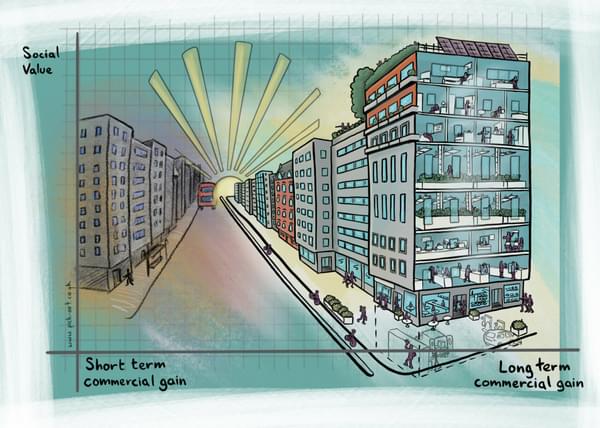

Looking at good examples of cities around the world, those where cycling is more prevalent have lower air pollution, such as Amsterdam and Copenhagen. Manchester is set to build a Dutch-style protected cycle network, aimed to be suitable for anyone 12 years old and above to use. The first stage of this will connect one of its largest southern suburbs with the city centre all for less than £14 million.

Myth 4: “Cycle paths take space away from cars, causing congestion and increasing pollution.”

The network of Cycle Superhighways built in London is the largest of its kind in the UK. There has been a lot of debate in recent years as to the effect this has had on congestion and pollution.

A typical example is Cycle superhighway 3, which travels along Embankment and cuts through the most polluted road in London; Upper Thames Street. Work began on the path in early 2015, which took a lane of traffic away from motor vehicles, before the cycle lane opened in 2016.

Kings College London have been recording roadside NO2 concentrations at monitoring stations along various routes, including on Upper Thames Street every hour since 2008. Their findings showed that, contrary to popular opinion, daily average concentrations dropped sharply since the path was built (see graph below).

Myth 5: “We are exposed to the highest levels of air pollution when outdoors.”

When you say air pollution, you might think of enormous industrial chimneys belching smoke or dual carriageways clogged with commuters. However, one of the key focuses of the Government’s Clean Air Strategy, published in 2018, was indoor air pollution. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) are produced by personal care products, air fresheners, cleaning products, paints and furniture. Guidance labels have been proposed to inform people of the potential risks, with some examples below.

As well as VOCs, NO2 concentrations when cooking can be significantly higher than heavily polluted streets. Most kitchens have hoods that condense steam and filter grease, but very few actually extract to the outside and simply recirculate NOx emissions from the gas hob.

Adequate ventilation is important, but does not necessarily equate to good indoor air quality. CIBSE has long recommended an overhaul of the Building regulations Part F and The Clean Air Strategy promised to review this in Spring 2019.

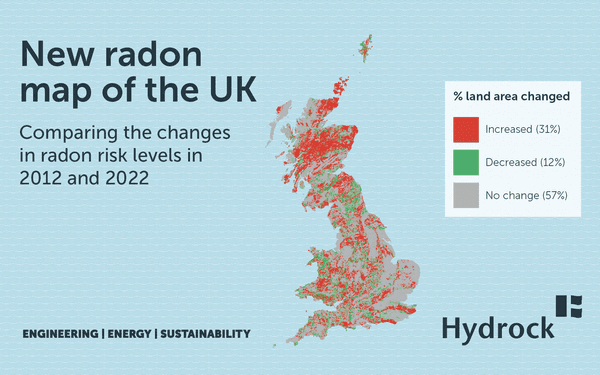

Myth 6: “Urban energy centres will add to city centre air pollution.”

Large Combined Heat and Power (CHP) energy centres and waste incinerators have become more popular in UK urban areas in recent years, leading to concern they contribute to urban air pollution. But what many people fail to take into account is that individual homes with gas boilers are also a source of pollution, especially when cumulated in densely populated areas.

After gas cookers, the closest pollutant source to our homes is often the flue of a gas boiler, located in many cases right next to windows (see image below). Whilst total emissions are much lower than from a busy road, their proximity to our living spaces makes them more of a danger.

At Hydrock we were interested in pollutant concentrations at our homes, especially as little research has been done in this area. Fifteen employees each took two diffusion tubes to put up at their houses to measure our exposure to NO2. One was placed at the front and one was placed at the back of the house. Everyone who had a gas boiler at the rear of their house obtained the highest reading there. Investment in district energy networks would offer a solution to this problem.

Instead of individual gas boilers, producing heat in a central location and piping it to houses using district heating networks means not only are the emissions sent up a chimney, away from sensitive receptors, but additional mitigation can be applied to that stack to reduce concentrations even further.

Energy efficiency over emissions technologies

If we take a step back and look at the reasons for pollutant emissions, the elephant in the room is our energy consumption. For example, to move an average person in an average car at 20mph requires 16 times the energy of someone riding an electric bike at the same speed. If that car drives at 30mph this increases to 36 times more total energy than the bicycle. Add to this the inefficiencies of an internal combustion engine (only 20% of the energy in a tank of petrol goes into moving the car, the rest is lost, mostly as heat) and the 30mph car uses 144 times the energy of a person on an electric bike. Make that car an SUV and it is over 200 times.

Similarly, making houses as energy efficient as possible, is the most effective way to minimise emissions from combustion in our back gardens or at centralised CHP plants.

Air pollution is a serious health threat and the UK is struggling to meet its pollution targets. We know, more than ever before, how important it is to ensure air pollution levels are as low as possible. Focusing on energy instead of emissions technologies brings a host of other benefits, such as quieter, safer and less congested cities and warmer homes that are cheaper to run.

Find out more about Hydrock’s specialist air quality services.