Hand on heart, do we have the faintest idea of what the world of travel and commuting is going to look like in five or ten years’ time?

Following his re-election, Mayor of Greater Manchester Andy Burnham made it known that finalising the Greater Manchester Spatial Framework is among his top priorities. One of his plans is to create a “London-style transport system” for the city-region, re-introducing bus franchising to the region for the first time since 1986.

That last point has really got my brain ticking. To make lasting progress, maybe we should be winding back the clock 50 years and identifying ways to re-create some common behaviours and values of that time, such as pride for our local towns and desire to use public transport as a means to getting around. Let me explain…

I’ll hold my hands up now, I blissfully lived in the privileged city centre bubble of Manchester for years, with the world at my doorstep and little need for a DeLorean. Even having relocated to Urmston, the city centre remains only seven miles away, which means an easy cycle, train or tram ride home.

“That last point has really got my brain ticking. To make lasting progress, maybe we should be winding back the clock 50 years and identifying ways to re-create some common behaviours and values of that time, such as pride for our local towns and desire to use public transport as a means to getting around.”

But I grew up in Oswaldtwistle on the outskirts of Blackburn. Despite being only 25 miles away, my family visited Manchester seldomly.

Blackburn is also often remembered for its 4,000 [pot] holes, thanks to The Beatles. Perhaps the allusion being made by John Lennon et al was that the town wasn’t fit for modernity. More likely, faced by changing behaviours and demographics, the local authorities simply couldn’t afford or justify resisting density. I mean, destiny.

As people became richer and cars cheaper, the nature of travel shifted drastically. In 1952 only 30% of distances travelled in Britain was by car, van or taxi; by 1970 that had risen to 75% and has since peaked to a constant 85% today.

For satellite towns, the accessibility of individual car ownership created complex problems and became the catalyst for decline and its legacy has come back to haunt us in the rear window.

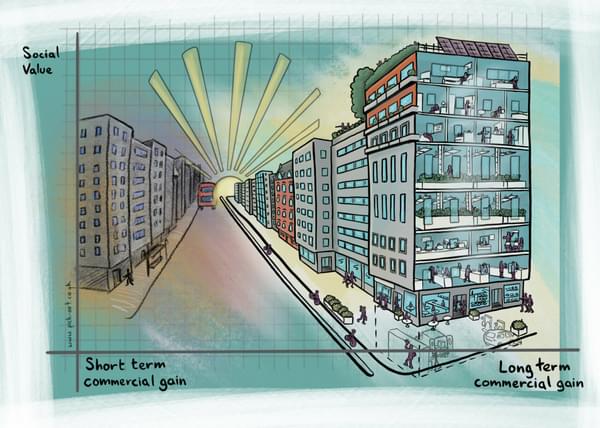

The bustling metropolis became where local people aspired to live, work and spend their hard-earned money. In a familiar asymmetry, this provided the incentive for increased inward investment which might have gone elsewhere. Town centres were essentially archived.

But the current climate crisis and the pandemic have shifted sentiment ‒ folk have fallen in love with their local town centres again. Meeting this groove like a stylus on vinyl, the government is giving 72 declining high streets around the country a share of £830m of funding to help reshape them for future communities.

For local authorities up and down the country, we know that public transport is key to so many of the agendas that matter. Decarbonisation being at the very top. Getting more people to adopt public transport and active travel will reduce our carbon emissions, improve our air quality, and create more sustainable communities.

“For local authorities up and down the country, we know that public transport is key to so many of the agendas that matter. Decarbonisation being at the very top. Getting more people to adopt public transport and active travel will reduce our carbon emissions, improve our air quality, and create more sustainable communities.”

Although we hear so much about electric vehicles (EV) being the answer to decarbonising our urban communities, there’s still no genuinely realistic route to net zero carbon emissions by 2050 that involves simply electrifying our current mix of journeys.

Several North West schemes are taking this very seriously and adapting their offer.

One example is in Merseyside, where St Helens Borough Council is transforming its infrastructure around one of its main railway stations as part of its Southern Gateway Highways Scheme. Having been awarded funding from Liverpool City Region Combined Authority, the council has plans for a network of connected cycle routes and pedestrian footpaths to encourage local residents to embrace a healthier lifestyle and better connect people to the town.

We’ve advised on concept designs drawn up for a network of almost seven miles of cycle routes and the Liverpool City Region’s first Cycle Optimised Protected Signals (CYCLOPS) junction ‒or CYCLOPS ‒which gives priority to cyclists and pedestrians and is loosely based on the Dutch-style roundabouts seen across parts of Europe.

Balancing heavily populated cities with the need for more green spaces isn’t quite as clear cut as knocking concrete down and adding more parks and trees. It’s going to take joined-up thinking to meet complex needs.

In Manchester, the proposed Ancoats Mobility Hub plans to combine shared electric cars and e-bikes with a last mile delivery consolidation centre, which we’re providing consultancy on. The transformational development challenges the conventions of parking, street usage, mobility, and logistics in a city centre environment.

One aim is to reduce the use of existing small pay and display car parks in the area and discourage on-street parking in order to eventually phase these out to make room for more public open space areas, including cycling and walking routes.

The hub offers the community a neighbourhood depot for people to collect from, eliminating excess “last-mile” courier journeys, small commercial retail units, a cycle hire scheme, and a ‘car club’ for locals. While serving existing residents of Ancoats, it would also meet the needs of future communities associated with the 1,616 new homes and up to 31,000 sq ft of commercial space identified within the Poland Street Zone Neighbourhood Development Framework.

Integrating the scheme in a sensitive way with the natural, local green space will be the key factor with the façade of the hub being as environmentally-friendly as possible, adopting living walls, photovoltaic panels and a sustainable energy supply.

Ultimately, we need to provide better connectivity to all cities, towns and suburbs in a cost effective and sustainable way.

“Ultimately, we need to provide better connectivity to all cities, towns and suburbs in a cost effective and sustainable way”

How about reutilising existing infrastructure? For example, breathing new purpose into existing railway lines such as the East Lancashire Railway line serving Bury, Ramsbottom, Heywood and Rawtenstall, which now only operates at the weekends for leisure trips onboard steam trains. If extended, infrastructure like this could provide greater connectivity to these suburbs, which would in turn lead to more inclusive growth.

Would it be utopian thinking to consider a future where the majority of short inner and outer city trips are made by a combination of shared pedestrian / cycle lanes and public transport, rather than sitting in congested traffic?

Innovation doesn’t always require novel-thinking, the tools can be found in the past with some subtle re-purposing and an open mind.

In the 1985 film Back to the Future, Dr Emmett (“Doc”) Brown exclaims "Roads? Where we're going [2020], we don't need roads."

As the final thought about our direction of travel, I’d suggest: "More Roads? Where we're going [2050], we don't need more roads."

This article originally featured in Place North West in July 2021