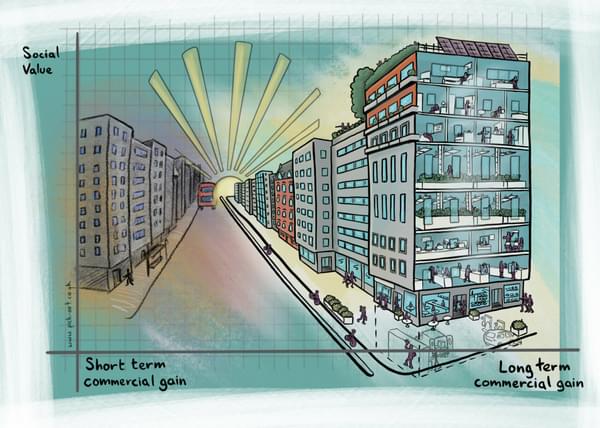

Our urban planning approach must pay greater attention to the intrinsic relationship between built form, sustainable mobility and social welfare, and their collective role in fuelling an intellectually stimulated society.

Whether reflected in self-inflicted housing shortages, affordability crises or environmental concerns, our current housing model is flawed.

Does the answer, and therefore opportunity, lie in urban form?

The art of urban form

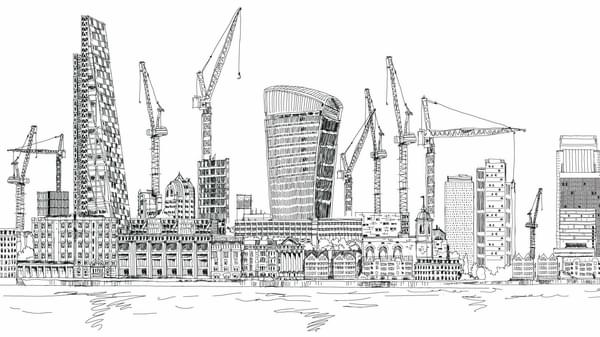

Comparing UK and European cityscapes reveals two key differences in support of critical mass: cities on the continent have more extensive mass transit networks and higher urban density.

Both of these points are inter-linked and the result of better planning and development.

Thriving mid-rise neighbourhoods are ubiquitous, developed around well-defined public transport corridors, often in the form of tree-lined boulevards, and festooned with a selection of ground floor street-facing amenities.

In the UK, our small and increasingly saturated city centres diffuse rapidly into sprawling low-density housing estates, two-storey buildings and car-centric infrastructure.

An indictment of our planning system, this urban form is egregiously expensive and has amplified carbon emissions, reduced economic productivity, segregated communities and heightened pressure on public services.

In short, it’s making our cities less healthy, less wealthy and less equitable.

Economic productivity

Studies have shown that UK cities underperform compared to their European counterparts, which costs the UK economy billions every year.

Their inferior ‘effective size’ is due to lower public transport accessibility, which can be attributed to the lower density, and results in a reduced labour market and diminished agglomeration effects.

Our cities are only ‘big’ on paper, they don’t get denser with size and a lack of connectivity inhibits their economic performance.

The low-density sprawl reduces the demand, patronage and viability of mass transit schemes, requiring more investment and expansion to achieve similar levels of permeability.

The development trap

The concept of induced demand posits that building more roads eventually leads to more congestion.

Yet, we’ve failed to appreciate the paradox and the ‘development trap’ has made new road infrastructure essential for an insatiable sprawl of low-density communities.

The systemic issues Britain faces are a consequence of the reaction to its previous post-WWII housing crisis. While Europe embraced higher density apartment building and invested in rapid transit systems, we favoured suburbanisation and heavy road construction.

Will we learn from history or further perpetuate this myopic and parochial charge?

Time for planning reform

Is our planning system to blame?

Zonal systems in European cities foster higher density mid-rise urban form, with minimum density targets mandated for areas surrounding transit stops.

In contrast, the UK’s discretionary system invites objections to individual applications rather than constructive engagement at the initial policy formulation stages.

This is evident in our regional cities, where brownfield land in central locations has been underdeveloped for decades. Conversely, there’s an endless supply of new cul-de-sac housing.

Cities like Manchester have been redressing this in recent years, but it’s still behind the curve. Reversing decades of socioeconomic damage demands an aggressive counter-policy.

High density doesn’t have to mean high-rise

Building higher density inner city neighbourhoods close to transport hubs would leverage existing resources, improve accessibility, limit carbon emissions, reduce car reliance, address our housing shortage and help grow productivity to internationally competitive levels by increasing the size of our cities.

You only need to look at the skyline to appreciate the progress of Manchester and Salford in recent years, with thousands of new apartments delivered, creating vibrant urban communities. Let the evolution continue.

However, the shift doesn’t have to be as drastic as the juxtaposition of 60-storey towers flanking one side of the Mancunian Way and two-storey houses the other. Small adjustments, such as adopting mid-rise (4–8 storey) apartment blocks seen across Europe, could be just as effective.

By giving more consideration to green spaces, urban retreats and school provision at the masterplanning stage within a reformed planning framework, we’d attract more families and achieve less superficial city centres.

Let’s talk about vertical expansion

While it would be easy to lay sole blame on our planning system, it’s only part of the problem. Behind policy lie societal misconceptions and deep-seated aversions to densification.

How beholden are we to the pursuit of suburban happiness? Can we afford to sweep our apartment living antipathy under the carpet and espouse the misconception that they’re transient dwellings for students and young professionals?

Instead, let’s take inspiration from the more egalitarian urban planning principles that have shaped the great continental cities, where city centres have a more balanced intergenerational populace. It transforms them into community-focused places for people to live, start a family and grow old.

For this to happen, apartments need to become aspirational places for everyone. Most European apartments feature spacious rooms, high ceilings, solid walls, dual-aspect windows, sizeable balconies, private communal gardens and excellent views, which make them attractive to families.

Sustainable public transport

The symbiotic relationship between higher density and better accessibility must be recognised and supported by our planning system.

Granted, there’s a vision for a ‘London-style’ public transport network in Greater Manchester. However, to be truly effective, a London-style system requires London-style density.

Greater density ensures more efficient use of land and resources and increases demand and viability of transit systems, marginalising malicious NIMBYism in the process.

The UK is one of the most densely-populated countries in Europe (and more so than China), yet has one of the lowest density housing models.

With just 20% of our populace living in apartments, the UK sits behind only Ireland and Norway.

We need to overhaul our planning system to drive profound urban change and create more effective cities, rather than another heuristic approach.

This article originally featured in Place North West Insights in October 2023. Photos via Shutterstock.

Explore related

- Articles

James McNay comments in RICS Built Environment Journal: Compliance with guidance may prompt safety complacency

Read more- News

Mark Walker comments in Green Street News: Could healthcare revive the heartbeat of our high streets?

Read more- News

Hydrock assists GRAHAM in achieving industry accreditation for carbon management system

Read more- News

Lights, Camera, Action! Sunderland gets set for Hollywood with planning approval of Crown Works Studios

Read more- News

Ground-breaking study provides valuable insight into construction innovation in north east England

Read more- Articles

How the London Plan sets the example for consistency in climate-related policy making

Read more- Articles

Decarbonise for less: unleash the cost-saving power of the Energy Savings Opportunity Scheme

Read more- News

Hydrock’s fire safety experts support planning application for new R&A project in St Andrews

Read more- News

Leading the way: Hydrock crowned Engineering Consultant of the Year at Building awards

Read more- Articles

Our Time to Lead session: The higher education sector and the Building Safety Act

Read more- Articles

Building safety regulations: Time to Lead — Can the building industry regulate itself?

Read more- News

Hydrock brings expertise to NHS estates programme to help meet sustainability and safety goals

Read more- Articles

Why 'just add mass' is no longer an acoustic solution in a carbon conscious world

Read more- Articles

Navigating the electrifying world of EV charging investments: Making 'big data’ central to due diligence

Read more- News

Ground-breaking land contamination conceptual model paves the way to a cleaner and safer future at Sellafield

Read more- News

Data centres, fire risk and the digital golden thread of information: Hydrock contributes to Fire Middle East

Read more- News

Peter Sibley comments in Building Magazine: Will Sunak’s ‘plan for growth’ be a magnet for future investment?

Read more- News

Hydrock’s award-winning streak set to continue with multiple shortlistings at Insider South West Property Awards 2023

Read more- Articles

Why the UK government’s case for investment in new oil and gas production is flawed

Read more- News

James McNay joins HSE Industry Competence Committee (ICC) to guide safer building construction for everyone

Read more- News

Hydrock shortlisted for Consultancy of the Year at Insider Yorkshire Property Awards 2023

Read more- News

Celebrating International Women in Engineering Day 2023: A journey of empowerment and growth

Read more- News

Hydrock strengthens national MEP division with new healthcare sector lead: Accelerating innovation in sustainable healthcare engineering

Read more- Articles

A two-tier system? Why we must embrace the digital golden thread across the built environment

Read more- Articles

Mark Pearce comments in Fleetworld: How can ChargeUK enable fleets to go electric with confidence

Read more- News

Hydrock bolsters transport planning offer with acquisition of Fore Consulting Limited

Read more- News

Ric Hampton comments in Property Week: The state of the UK’s film and TV studio market

Read more- Articles

The Building Safety Act's second staircase consultation: the easy way out for politicians as well as residents?

Read more- News

Hydrock shortlisted for Insider North West Property Awards in its silver anniversary year

Read more- Articles

NHS Trusts need to be ‘fund-ready’ to maximise Government’s decarbonisation support

Read more- Articles

The Building Safety Act: Is the building industry sleepwalking into a new regulatory regime?

Read more- Articles

Interview: Ric Hampton appointed to Bristol Nights Advisory Board to support nightlife & culture

Read more- News

Building with Nature accreditation emphasises importance of green and blue infrastructure

Read more- News

Hydrock ranks #2 nationally and #1 regionally in three Best Companies 2023 league tables!

Read more- Articles

Hydrock comments in Building: The Building Safety Act and what the second staircase rule would mean for high-rise blocks

Read more- Articles

Hydrock roundtable: Diversity and access to careers in the built environment sector

Read more- News

Hydrock joins Task Group for delivery of UK’s first Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard

Read more- Articles

Hydrock comments in Building: Strong and stable? This government is anything but when it comes to energy infrastructure

Read more- News

Hydrock adds leading technical specialist to its civil and structural team in Yorkshire

Read more- News

Zuzanna Bialkowska awarded ‘Up-and-Coming Fire Engineer’ of the year by The Society of Fire Protection Engineers

Read more- News

Hydrock shortlisted for Engineering Consultant of the Year at the Building Awards 2022

Read more- News

Hydrock appointed to deliver catheterisation scanner suite at St Bartholomew’s Hospital

Read more- News

Extreme heat: how UK buildings and infrastructure are dangerously ill-equipped to cope

Read more- News

Simon Cole joins Hydrock as leading technical specialist for Geo-Environmental and Geotechnical division

Read more- News

Hydrock selected for specialist public sector consultancy framework in the North East

Read more- News

Hydrock's Acoustics division joins industry-recognised Association of Noise Consultants

Read more- News

Hydrock nets geo-environmental and geo-technical role on multi-million-pound Belle Vue Academy site

Read more- News

Hydrock support successful planning application to extend Western Community Hospital in Southampton

Read more- News

Hydrock’s Civil & Structural engineering team appointed on next stages of £104m Patchworks development

Read more- News

Hydrock supports feasibility and planning application on Grade II listed buildings in Leeds

Read more- News

Shortlisted for Consultancy of the year at the Insider Wales Property Awards for second year running

Read more- News

Fire Risk Management team secure industry-recognised fire risk assessment accreditation

Read more- News

Hydrock celebrates seventh consecutive year in UK’s 100 Best Large Companies to Work For

Read more- News

Hydrock & KTA logistics specialists advise on 1m sq ft reserved matters application at Magna Park North

Read more- News

Civils & Structures team move to detailed design with Mi-space on 4.65ha Barne Barton site

Read more- News

Former KPMG Partner and Board Member, Ronnie McCombe joins Hydrock as Non-Exec Chairman

Read more- News

Industry-leading clean energy specialist joins Hydrock to power growth of Smart Energy & Sustainability business

Read more- News

Hydrock secures appointment on Higher Activity Waste framework through Accord Consortium

Read more- News

Hydrock advising BoKlok – the Skanska and IKEA joint venture modular housing business

Read more- News

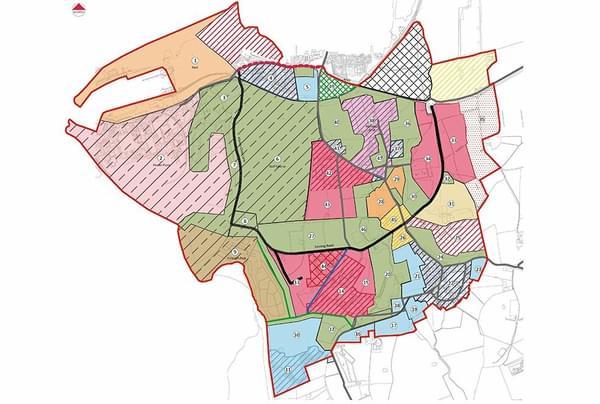

Hydrock on the strategic masterplan team for Cyber Central Garden Community, Cheltenham

Read more- News

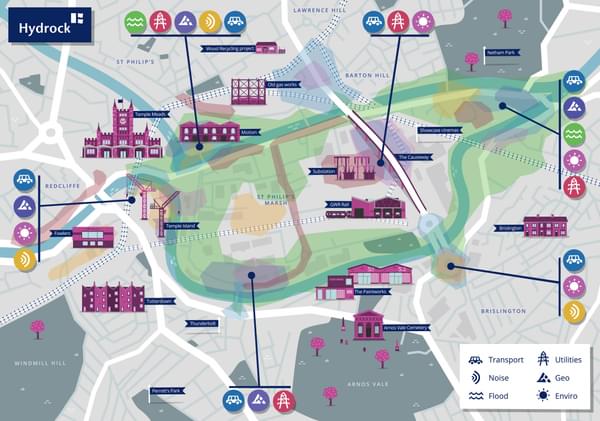

Hydrock's multi-disciplinary expertise helps unlock massive residential site in Bristol

Read more- Articles

What do proposed changes to building regulations mean for energy efficiency standards?

Read more- Articles

If electric vehicles are the future, how will that affect the electricity demands of a site?

Read more- News

Rapidly expanding Smart Energy team hires international expert in decentralised energy

Read more- News

Hydrock Nuclear divisional director, Peter Sibley, appointed to Nuclear Industry Council

Read more- News

Stunning new headquarters for English National Ballet unveiled by London mayor, Sadiq Khan

Read more- News

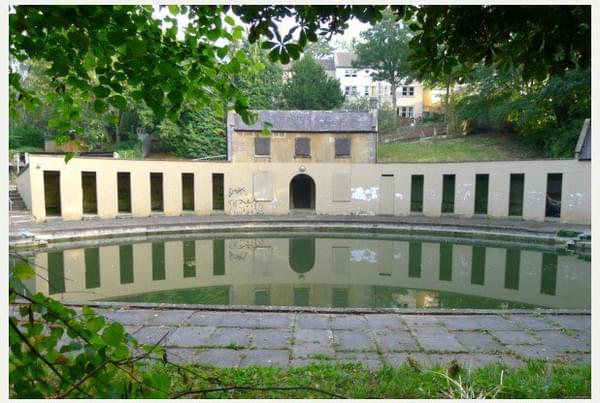

Hydrock provides engineering services to transform Grade II* listed Cleveland Pools lido in Bath

Read more- News

INWED 2019 – a site visit to The Wave, Bristol, inspires local schoolgirls about engineering

Read more- News

Transport team contribute to successful planning submission to revive Andrew Gibson House, Merseyside

Read more- News

From History Graduate to Utilities Consultant: My unexpected route into engineering (as a girl)

Read more- News

Multi-disciplinary advice helps secure planning for landmark footbridge in Pontypridd

Read more- News

Ground investigation work contributes to planning application for 282 homes in Stretford, Manchester

Read more- News

Hydrock helps secure planning for refurbishment of historic Generator Building, Bristol

Read more- News

Civil and structural design underway for new homes on former Nestlé site in west London

Read more- News

Ground-breaking initiative to provide affordable housing to transform lives of Bristol’s young homeless

Read more- Articles

The balance of power - meeting unpredictable future energy demands in a rapidly changing environment

Read more- News

The University of the West of England (UWE) appoints Hydrock to design new multimillion pound engineering building

Read more- News

Hydrock supports Linkcity with planning submission for 375 new homes in central Bristol

Read more- News

Double win at RICS South West Awards: Commercial Project of the Year and Building Conservation Award

Read more- News

Hydrock wins ‘Best Place to Work’ at inaugural Construction Investing in Talent Awards

Read more- News

Delivering key infrastructure assessments for proposed strategic rail freight interchange

Read more- News

Hydrock’s highways and infrastructure advice helps secure planning approval for 345,000 sq ft industrial unit at CORE 42

Read more- News

Hydrock appointed to appraise transport issues within historic Porthcurno Valley, Cornwall

Read more- News

Hydrock’s transportation team help secure planning on 400-bed student scheme in Bournemouth

Read more- News

Hydrock delivers the multi-disciplinary engineering design on two middle schools in Rhondda Cynon Taf

Read more- News

Kier appoints Hydrock to design Bristol Aerospace Centre – the permanent home for Concorde

Read more- News

Daniel Beynon joins Hydrock in Cardiff as Technical Director for Building Performance Engineering

Read more- News

Appointed to support the delivery of world-class resources for the UK’s agri-tech sector

Read more- News

Steel frame designed for Bright Bricks’ 160,000 piece LEGO® version of the Soyuz Capsule

Read more- News

Hydrock appointed by John Sisk & Son Ltd to deliver works on Manchester Life development

Read more- News

Acoustic engineering capability further strengthens Hydrock's building design services

Read more- Articles